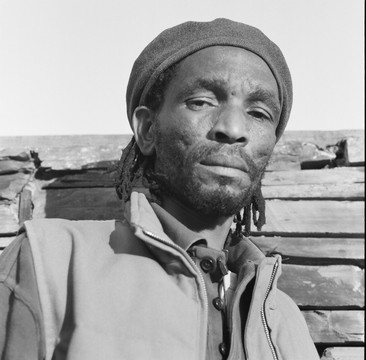

Lesego Rampolokeng

*1965 ZA, South Africa

Lesego Rampolokeng was born on 27 July 1965 in Orlando West, Soweto when South Africa was still under apartheid. The violence of this state system and the opposition it provoked, with all the accompanying effects (so-called collateral damage), shaped him from childhood. His father, exhausted by the arduous work in a platinum mine, died so early that he never had a chance to get to know him. His mother, who worked as a toolmaker in a factory, brought him up single-handed. He was raised a strict catholic and, in an interview with the Swiss weekly newspaper "WochenZeitung", chose the use of images from the bodily sphere as an extremely direct means of depicting the results of violence: "Catholicism wants to make people sterile and clean. Bodily functions, the whole of sexuality, are associated with shame. The Virgin Mary is this totally untouched figure. Not to mention the halo above the head of the tiny, oh so sweet, child: complete purity. When we look at the role religion plays in oppression throughout the world… even apartheid was vindicated using the Bible. The colour of my skin - which I consider beautiful - is associated with excrement. I have to ask myself where that comes from. The answer lies in the Catholic Church." His mother remarried and the family name changed to Rampolokeng. Lesego (which means "all the best") was eleven at the time of the schoolchildren´s revolt in the townships of Soweto in which hundreds were shot dead. He too rebelled. He began writing at an early age, and attributed this to his situation of oppression: "I was brought up to celebrate my own slavery. To me, what people call poetry became the means of explaining the world to myself." His step-father made him study law at the University of the North, but he broke off his studies, founded a family and, in a desperate effort to lead a middle-class existence, he forced himself to work for all of seven months at the stock exchange in Johannesburg. But it was to no avail: Lesego Rampolokeng is a poet, and he leads the life of a poet. He went public with his poetry: at first in schools, university lecture halls, on street corners, in meeting halls, at poetry readings, festivals and events - in South Africa, the neighbouring states, in Europe and America. In his introduction to "Horns for Hondo", published in 1990 by Cosaw in Johannesburg, Andries Walter Oliphant wrote about the background to Rampolokeng´s poetry: "This world of human degradation \... does not simply involve a hierarchical classification of human beings. It also refers to a situation in which people are tramped upon and trampled. The social order is premised on violence and murder. Every sphere of social life and every turn in history is haunted by horror. Walter Benjamin´s thesis that ´every document of civilization is simultaneously a document of barbarism´ is particularly apt with regard to Rampolokeng´s work. The stains of dehumanisation, splashed over and seeped into the social and psychological fabric of South Africa, are made visible in his poetry (...). It is therefore not surprising, that the overriding tone of Rampolokeng´s work is revulsion and condemnation of this dehumanising order. His denouncement couched in biblical and juridical imagery is unremitting. This is so, even when he strikes a humorous cord. The only irony he allows himself and us is directed at those who pose as literary arbitrators." To begin with Lesego Rampolokeng was celebrated primarily as a rap poet, but now he increasingly rejects this limited categorisation of his work. In an interview last year with the Swiss weekly paper "WochenZeitung" he said: "In the late seventies I was involved in the Black Consciousness Movement. We wanted first to break the mental chains, to give up our slave mentality. Without this there could be no political liberation. We were interested in what people like Malcolm X, Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh did. And so the things sung about by Gil Scott Heron in the USA and Linton Kwesi Johnson in Britain were important to us too. But that doesn´t make me a rap poet. \.... We live in a global Potemkin village. Political hip-hop is no longer important to young people in South Africa. \... At the beginning hip-hop had something to say, it was on the margins of capitalist society. But when it started gaining in significance, it was absorbed by the system. That bothers me." But Rampolokeng does work with rock and hip-hop musicians, with DJs such as Temba, and with different musical formations such as the "African Axeman" with Bafana Khumalo, or in Berlin with Souleiman Touré. He is not interested in "this street corner materialism" which makes rappers keep asking for payment. As a poet he earns his livelihood from readings (especially in Europe), writing for the theatre, for example "Faustus in Africa", which was written for the Handspring Puppet Company and performed with great success in Europe in 1995, and sometimes by writing on commission. But he is not one to talk about poetic freedom: "Freedom? To me poetry is Sisyphean labour. I know that everything I try to handle is far greater than I could ever be. But maybe the very impossibility of winning the battle is what attracts me to it." His works bear witness to this: the courage to clearly name the horrors, the gut feelings of participation in the depicted events and the strength to concentrate this into poetic form. No matter how clearly Lesego Rampolokeng defines the contours of formal perception, the reconstructed occurrences are acutely palpable and always expose the inherent aberrations. This is what makes the texts so uniquely relentless - relieved only by the strict form that creates distance, giving the reader space to take up a position and see these "fruits of anger" as they are: an expression of the unbearable. Many of his poems can be appreciated in German thanks to the dedicated work of Thomas Brückner who has translated them, capturing their mood and atmosphere, their emotions and imagery. On the relationship of the readers and listeners to his poetry Lesego Rampolokeng says: "People like things that are beautiful. I don´t write about beautiful things. When you see how teenagers attack a man who sells milk and hack off his arms to slurp yoghurt from the open wounds, that´s nothing beautiful. How can people like it when I write about things like that? The Nobel prize winner for literature, Nadine Gordimer, wanted to drag me off to her personal analyst; she reckoned I was sick. Is it me who´s sick, or the things I write about?”